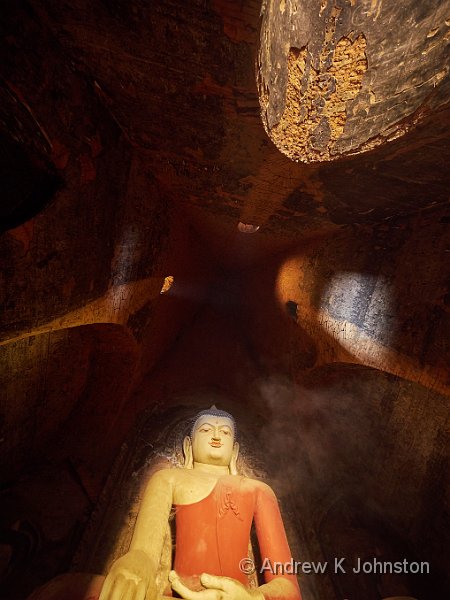

| Buddha at Pa-Hto-Thar-Myar Pagoda, camera lying on bag! | |

| Camera: Panasonic DMC-GX8 | Date: 11-02-2017 12:14 | Resolution: 4072 x 5429 | ISO: 400 | Exp. bias: 0.66 EV | Exp. Time: 1.6s | Aperture: 4.5 | Focal Length: 7.0mm | Location: Pa-Hto-Thar-Myar Pagoda | State/Province: Nyaung-U, Mandalay | See map | Lens: LUMIX G VARIO 7-14/F4.0 | |

The Perfect is the Enemy of the Good. I’m not sure who first explained this to me, but I’m pretty sure it was my school metalwork teacher, Mr Bickle. Physically and vocally he was a cross between Nigel Green and Brian Blessed, and the rumour that he had been a Regimental Sergeant Major during the war was perfectly credible, especially when he was controlling a vast playing field full of chatty children without benefit of a bell or megaphone. However behind the forbidding exterior was a kindly man and a good teacher. When my first attempt at enamel work went a bit wrong, and some of the enamel ended up on the rear of the spoon, I was very upset. He kindly pointed out that it was still a good effort, and the flaw "added character". My mother, another teacher, agreed, and the spoon is still on her kitchen windowsill 45 years later.

I learned an important lesson: things don’t need to be perfect to be "good enough", and it’s better to move on and do something else good than to agonise over imperfections.

I also quickly found that this is a good exam strategy: 16/20 in all five questions is potentially top marks, whereas 20/20 in one and insufficient time for the others could mean a failure. The same is true in some (not all) sports: the strongman who is second in every event may go home with the title.

Later, in my training as a physicist and engineer, I learned a related lesson. There’s no such thing as an exact measurement or a perfectly accurate construction. I learned to think in terms of errors, variances and tolerances, and to understand their net effect on an overall result. When in my late 20s I did some formal Quality Management training the same message emerged a different way: in industrial QA you’re most interested in ensuring that all output meets a defined, measureable standard, and the last thing you want is an individual perfectionist obstructing the process.

Seeking perfection can easily lead to a very low (if high quality) output, and missed opportunities. It also risks absolute failure, as perfectionists often have no "Plan B" and limited if any ability to adapt to changing circumstances. "Very good", on the other hand, is an easy bedfellow with high productivity and planning for contingencies and changes.

I adopt this view in pretty much everything I do: professional work, hobbies, DIY, commercial relationships, entertainment. I hold myself and others to high standards, but I have learned to be tolerant of the odd imperfection. This does mean living with the occasional annoying wrinkle, but I judge that to be an acceptable compromise within overall achievement and satisfaction. Practice, criticism (from self and others) and active continuous improvement are still essential, but I expect them to make me better, not perfect.

The trick, of course, is to define and quantify what is "good enough". I then expect important deficiencies against such a target to be rectified promptly, correctly and completely. In my own work, this means allowing some room for change and correction, whether it’s circulating an early draft of a document to key reviewers, or making sure that I can easily reach plumbing pipework. If something must be "set in stone" then it has to be right, and whatever early checks and tests are possible are essential, but it’s much better to understand and allow for change and adjustment.

In the work of others, it means setting or understanding appropriate standards, and then living by them. After I had my car resprayed, I noticed a small run in the paint on the bonnet. Would I prefer this hadn’t happened? Yes. Does it prevent me enjoying my unique car and cheerfully recommending the guys who did the work? No. Professionally I can and will be highly critical of sloppy, incomplete or inaccurate work, but I will be understanding of odd errors in presentation or detail, providing that they don’t affect the overall result or number too many (which is in turn another indicator of poor underlying quality).

So why have I written this now, why have I tagged it as part of my Myanmar photo blog, and why is there a picture of the Buddha at the top? In photography, there are those who seek to create a small number of "perfect" images. They can get very upset if circumstances prevent them from doing so. My aim is instead to accept the conditions, get a good image if I can, and then move on to the next opportunity. At the Pa-Hto-Thar-Myar Pagoda I (stupidly) arrived without my tripod, and had to get the pictures resting my camera on any convenient support using the self timer to avoid shake, in this case flat on its back on my camera bag on the temple floor. Is this the best possible image from that location? Probably not. Am I happy with it? Yes, and if I have correctly understood Buddhist principles, I think the Buddha would approve as well.

It is in humanity’s interest that in some fields of artistic endeavour, there are those who seek perfection. For the rest of us, perfection is the wrong target.

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed)

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed) Main feed (direct XML)

Main feed (direct XML)