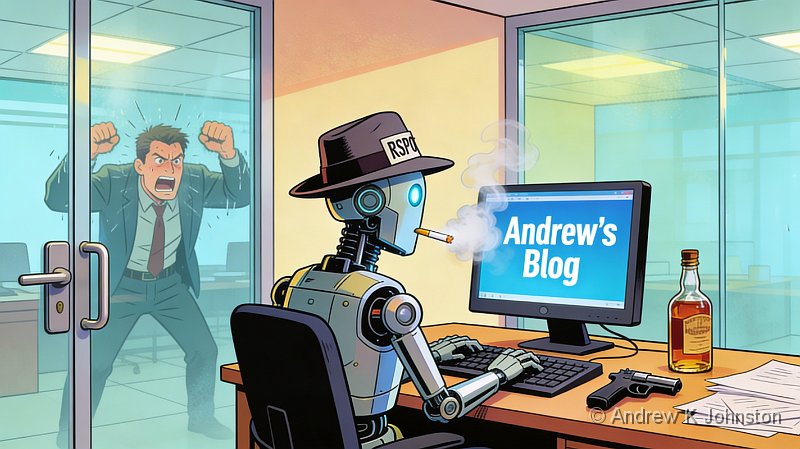

| Hunter S Robot writing blog |

Are we becoming the feckless race from The Time Machine? Can we resist the temptation?

Background

The second prompt was the recent publication of Matt Shumer’s essay Something Big is Happening in AI. That asserts that we are rapidly reaching (or may have already reached) “the singularity”, where AI starts to evolve at a speed outstripping our control, and displaces a large proportion of what we used to call “knowledge workers”, with dramatic societal impacts.

I was going to write the Eloi article myself, honest I was. But having read Matt’s article, I couldn’t help thinking “could AI do this?”. Could it do the research (I haven’t read The Time Machine for at least 40 years), reach reasoned conclusions with which I agree, and write in a style reasonably mimicking my own?

So I fired up the free version of ChatGPT with the following prompt:

Write an essay of 1300-1400 words, on the subject “Are We Becoming the Eloi?” Take as reference the race of the Eloi in H G Wells’ The Time Machine. Compare current societal trends such as an increasing reliance on automation, increased distance between users and underlying technology (with a commensurate inability to act if the technology is not working) and the increased anxiety and mental health issues of younger generations. Write in a style similar to this article: https://www.andrewj.com/blog/2025/adjustable-architecture-and-minimising-waste/

The result (see here) is very impressive, a detailed, reasoned essay analysing ways in which we are starting to resemble the Eloi, but also identifying key differences and ways in which we might escape that fate. It’s quite academic, with some philosophy references beyond my knowledge, but at a stretch I might pass it off as “all my own work”.

The main problem is stylistic. The article is more academic than I’d write, complete with valuable references. It’s wordy, in need of at least as much editing for verbosity and repetition as my own first drafts do. There are also odd issues with terminology. The article repeatedly uses the word “agency” with a meaning I don’t usually adopt, and has also invented a clumsy term which I would never use: “Eloi-ness”.

However, there’s a simple fix. In Red Dwarf there’s a wonderful scene where the rest of the crew are faced with two Dave Listers – one the real thing, the other a dangerous simulant who can copy his appearance and personality. Both are holding guitars. Both play, one badly and the other is sublime. Without a word the crew unanimously shoot the latter. The real Dave Lister can’t play the guitar, but he thinks he can, so that’s what the simulant does.

So I just need to instruct ChatGPT to write the article not as I actually write, but as I like to think I write… Prompt 2:

Write a similar essay, but make it less academic, and write in the style of Hunter S Thompson.

To put it bluntly, that nails it. The essay, below, captures almost all the concepts I wanted to incorporate, in a style which is both blunter and smarter than my own, but not so far removed you might not believe I wrote it myself on a good day.

The essay is presented exactly as generated, excluding minor tweaks to punctuation, and changing a couple of American spellings.

The Essay: Are We Becoming the Eloi?

In The Time Machine, Wells imagined the Eloi: pale, gentle, useless creatures drifting through a pastoral future where every need was met and every challenge long forgotten. They did not work. They did not invent. They did not even wonder very much. They simply lived in ornamental comfort while the unseen machinery of their survival ran elsewhere, managed by another species they barely understood.

It was a grotesque fable about class, complacency, and the slow erosion of capability. For a long time, it felt comfortably fictional: Victorian nightmare fuel, a warning directed at a distant future we were sure we would never resemble.

And yet here we are, living in a world where a great many people cannot boil an egg without consulting a search engine, cannot navigate a city without a glowing blue dot telling them where to turn, and cannot repair even the simplest device because every tool they own is sealed shut with proprietary screws and legal disclaimers. We are not helpless, not yet – but we are drifting in that direction with the serene confidence of people who believe the escalator will run forever.

Automation was supposed to free us. That was the promise: machines would do the dull work, algorithms would handle the complexity, and humans would finally be liberated to pursue creativity, leisure, and higher thought. In theory, it sounds magnificent. In practice, something stranger has happened. Instead of freeing us to become more capable, automation often encourages us to become less involved. It doesn’t just do the work – it removes the need to understand the work at all.

Consider how many systems you rely on daily that you could not repair, replicate, or even explain in broad terms. Your phone connects to a network you don’t understand, which runs through infrastructure you never see, governed by software you never touch, administered by people you will never meet. If the entire structure hiccups, your response is not to diagnose it but to wait – helplessly, irritably – for someone else to fix it. You are a passenger in a machine that does not require your participation, only your subscription.

The Eloi, in Wells’ nightmare future, were not stupid because they were born that way. They were stupid because their environment stopped demanding anything from them. Muscles that are never used fade; instincts that are never exercised disappear; curiosity that is never necessary grows quiet. The human brain is no exception. When every friction is removed from life – when navigation, memory, calculation, communication, and even entertainment arrive automatically – the temptation is not to grow wiser with our extra time. The temptation is to drift.

Look at the modern office worker staring blankly at a spinning “loading” icon, as if their entire professional identity has been unplugged along with the server. Watch the commuter pacing the platform because the ticketing system crashed and no one remembers how to process anything manually. Observe the mild panic that sweeps through a café when the contactless payment terminal fails and suddenly the ancient technology known as “cash” must be summoned from dusty wallets. These are not catastrophic events. They are small inconveniences. But the reaction they provoke, the sense that the world has temporarily become unmanageable, tells a deeper story about how far we have stepped back from the machinery that runs our lives.

Meanwhile, younger generations grow up inside systems that are even more abstracted. They do not learn how things work; they learn how interfaces behave. They swipe before they read. They troubleshoot by restarting the app. They store their memories in cloud servers whose physical locations might as well be on Mars. This is not a moral failing; it is simply the environment they were handed. But environments shape people, and an environment that constantly cushions failure also quietly erodes resilience.

There is a peculiar irony here. Never in history have humans possessed more knowledge, yet never has the average individual needed to know less to function day-to-day. A person in the nineteenth century might have needed practical familiarity with tools, navigation, mechanical systems, and local infrastructure just to survive ordinary life. Today, survival depends more on passwords than on skills. Forget the password, and you are locked out of your own existence. Forget how to mend a device, and you simply replace it. Forget how to navigate without GPS, and you circle the same block until the satellite signal returns like divine revelation.

This creeping dependency does something subtle to the psyche. When you no longer feel capable of solving problems directly, when solutions always arrive from outside, delivered by software updates or distant technicians, you begin to feel smaller in relation to the world. Problems seem larger. Systems feel opaque. Control appears theoretical rather than practical. Anxiety flourishes in precisely this kind of psychological climate: a world that is enormously powerful, endlessly complex, and largely inaccessible to individual intervention.

The rising tide of anxiety among younger people is often explained in terms of social media pressure, economic uncertainty, or educational stress. All of those factors matter. But there is another quieter ingredient: the persistent feeling of operating inside systems you cannot influence. When everything depends on infrastructure you cannot see and algorithms you cannot challenge, the world begins to feel less like something you shape and more like something that happens to you. The Eloi lived like that – pleasantly, superficially happy, but fundamentally detached from the forces that determined their fate.

Of course, the comparison has limits. We are not lounging in marble ruins eating fruit while subterranean creatures manage civilization. We build extraordinary things. We invent, argue, protest, experiment, and obsessively redesign our own technologies. But cultural direction matters, and the direction of modern convenience is unmistakable: fewer manual skills, less mechanical understanding, more automated decision-making, and an ever-widening gap between what systems do and what users comprehend.

The most dangerous aspect of this trend is not that machines are getting smarter. It is that humans are becoming more comfortable not needing to be. Intelligence, like strength, fades when unused. If every task that once required patience, memory, or ingenuity is replaced by a single button labelled “Optimize,” those faculties don’t vanish overnight. They simply stop developing. Over time, a society can become incredibly sophisticated at the macro level while individuals become strangely passive at the micro level, surrounded by miracles they cannot recreate and comforts they cannot maintain.

And yet, the situation is not hopeless. Far from it. The key difference between us and Wells’ fictional future is awareness. The Eloi did not know what they had lost. We still do. We still teach engineering, repair, science, navigation, and craftsmanship. We still debate the ethics of automation and the limits of artificial intelligence. We still celebrate people who understand how things work, even if the average citizen doesn’t always feel compelled to learn those skills personally. Awareness is the thin line that keeps a technologically advanced civilization from sliding into ornamental dependency.

The question, then, is not whether technology will continue to automate life – it absolutely will – but whether we choose to remain mentally and practically engaged with the systems we create. Convenience is not the enemy; indifference is. The danger is not that machines help us, but that we gradually forget how to help ourselves.

Picture the world fifty years from now. It could be a dazzling landscape of automated infrastructure, personalized AI systems, and seamless logistics, with citizens who understand enough of the underlying mechanics to intervene, repair, and innovate when necessary. Or it could be a comfortable garden full of passive consumers, bewildered whenever the machinery pauses, waiting patiently for unseen specialists to restore normality. Both futures are technologically advanced. Only one avoids the fate of the Eloi.

The warning hidden in Wells’ strange little novel is not that progress destroys humanity, but that comfort can quietly dissolve the habits that make humanity resilient. Skills unused fade. Curiosity neglected dulls. Agency surrendered becomes difficult to reclaim. And the transformation does not arrive with dramatic fanfare: it happens slowly, politely, wrapped in the reassuring language of efficiency and convenience.

So the next time the Wifi drops and the room falls into that anxious, humming silence, it might be worth resisting the instinctive panic. Look around. Ask yourself how much of the world you can still operate without the invisible scaffolding of automated systems. Not because you intend to reject technology – only a lunatic would do that – but because the ability to function without total dependence is the thin line between mastery and decoration.

The Eloi did not notice the moment they became helpless. That is precisely why we should.

Assessment

Much of my professional career hinged upon my ability to consolidate disparate sets of information, analyse and summarise them into a coherent whole, and then clearly communicate the expected impacts and options for action. A large part of that work can now be laid off to an AI.

That said, at least for now there’s a difference between “implement this well-formed idea” and “help me develop this idea”. It’s not clear how AI would fit into my 40-year-old tried and tested analysis process. I start with a blank document, or maybe a vague outline, and dump all sorts of ideas, notes, research material and other people’s contributions at the bottom. I then work down through all the material, delivering a curated and edited version into the document above. I eliminate the irrelevant or duplicated. Some material is included only to be refuted. The text is constantly refactored to ensure flow and coherent arguments. That process in turn generates ideas for further research, tests and writing.

For example, after reading the AI generated essay, I thought of two more potentially rich seams of analysis:

- Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895. Phones and electricity services were a recently-invented novelty. Distant communication was by letter or telegraph. Wells set the later scenes 800,000 years in the future, and failed to predict the exponential, accelerating changes which mean we are confronting these challenges after a mere 130 years. Does the speed of change impact on the effect it will have?

- In The Time Machine, the Eloi are supported by the dark, subterranean Morlocks. They manage the hidden technology but also prey upon the Eloi, for food. In a very literal sense the Eloi are not the customers, they are the product. This is clearly a powerful, if extreme, metaphor for the capitalist providers of our tech. That metaphor could be explored further.

AI could clearly be instructed to extend the essay with these concepts, but it didn’t initiate them. For now, I still have to have the ideas.

However, I can imagine an AI which keeps track of my writing ideas, and regularly prompts me with “what do you want to write next?”, takes my notes and comes up with a first draft. It would be trained to mimic my own style, not one to which I aspire. It could automatically prompt the image generator to generate some sample hero images with my regular cast of characters, like the puzzled bear. It could automate the posting process. I could become one of the most prolific bloggers, but at what point is the blog no longer mine, but a computer’s?

There’s an interesting difference between the two versions of the essay. The first, academic, version (see here) goes into quite a lot of detail on the mental health dimension, complete with supporting references. Despite being an explicit element of the prompt, this is only lightly touched upon in the second version. I’ve seen this before: stylistic guidelines can change not only the writing style, but may also impact on tone, direction and content.

The temptation to use AI is potentially overwhelming. Two 1400 word essays were each generated for me in less than a minute. Either could be used without further work. By comparison my introduction and assessment have taken at least 6 hours to write. If I was getting paid for this the temptation would be hard to resist.

Even where I need to write the words myself, I will now use AI for supporting tasks. My blog’s “hero” images are either my own photos, or AI-generated cartoons. If I was writing my project management book today I wouldn’t employ a cartoonist. And that’s another job gone…

However, I’m not sure there’s any evidence yet of “the singularity”. The main reason is I think we’ve got the wrong idea about it. AI doesn’t have to be fully sentient to cause harm. It doesn’t have to launch nukes or push us out of an airlock to cause profound societal change.

Instead, I think we are going to experience a series of inflection points in different disciplines. We may not notice many of them as AI rapidly accelerates towards and passes them, we will only recognise them in the rear-view mirror.

We have to understand how AI will affect society, and that brings us back directly to my own question. Are we becoming the Eloi?

The answer is probably “not exactly”. I don’t think we need fear a future in which we are all completely degenerate, farmed by a successor species, aliens (or machines, as in The Matrix).

But we may be headed very rapidly for a world in which we all display some characteristics of the Eloi, some of the time. We are already in a society in which a substantial subset feel things are done to them, not by them. Some of us will also be Morlocks, unless we somehow arrest the rise of exploitative corporate giants.

The speed of change is significant. Wells imagined a gap of 800,000 years, in which the Eloi have degenerated physically as well as mentally. In reality in that period a better-equipped species of Homo might evolve. Instead, we are trying to manage massive and accelerating mental and societal change with much the same physical provision as the first of our species.

I think the ChatGPT essay sums it up well: “The Eloi did not notice the moment they became helpless. That is precisely why we should.”

We need to be alert to the risks. As individuals we need to try and understand what we can, avoid always taking the easy way out, and sometimes deliberately “do it the hard way”. We also need to make sure those attitudes are inculcated into younger generations. We need to make sure our political decision-makers are also alert to the risks, and not blind-sided by the siren calls of big tech.

We don’t have to become the Eloi. But there’s a very real risk that we will.

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed)

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed) Main feed (direct XML)

Main feed (direct XML)