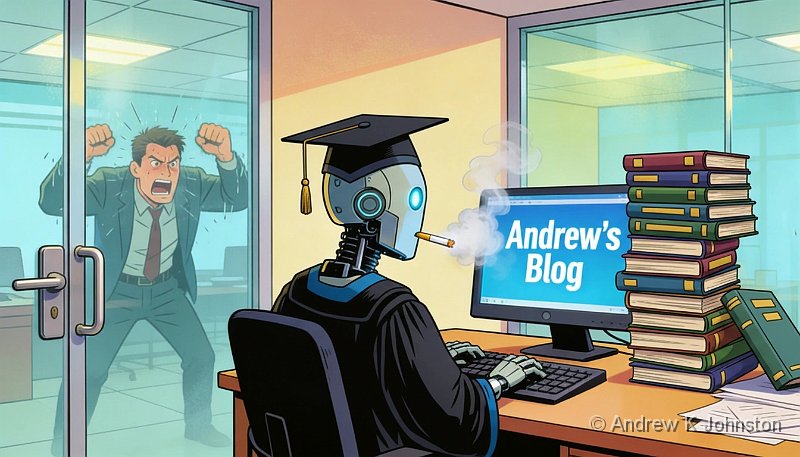

| Academic robot writing blog |

Introduction

This is an appendix to a more complete article, see https://www.andrewj.com/blog/2026/are-we-becoming-the-eloi-the-academic-version/

I was recently bemoaning our increasing dependency on automation and our general inability to take charge and either fix or work around broken things, and I thought of the Eloi. In H G Well’s The Time Machine, published in 1895, he imagined a distant future human race who live an apparently idyllic existence, but who have lost any ability to help themselves, and are to some extent just farm animals for the Morlocks, who prey upon them. In some ways, we may be approaching the society Wells foresaw. At the same time I read another essay asserting that AI is ready to displace a large proportion of what we used to call “knowledge workers”. I decided to test the latter assertion by asking ChatGPT to draft an essay on “Are We Becoming the Eloi?”.

I fired up the free version of ChatGPT with the following prompt:

Write an essay of 1300-1400 words, on the subject “Are We Becoming the Eloi?” Take as reference the race of the Eloi in H G Wells’ The Time Machine. Compare current societal trends such as an increasing reliance on automation, increased distance between users and underlying technology (with a commensurate inability to act if the technology is not working) and the increased anxiety and mental health issues of younger generations. Write in a style similar to this article: https://www.andrewj.com/blog/2025/adjustable-architecture-and-minimising-waste/

The essay below is what resulted. It’s presented exactly as generated.

For various reasons, I then went on to generate a second version, with different stylistic guidelines, which I use in the full article. However some readers may want to compare the two versions of the essay, so I’m providing the first draft here.

Are We Becoming the Eloi?

The Eloi and the Modern Soul

Wells’ Eloi are not merely idle; they lack intellectual curiosity, physical strength, and any meaningful connection to the systems that sustain them. They are the elegant unwashed, unaware that their comfort is the product of unseen labour — the Morlocks’. In The Time Machine, this absence of challenge corrodes their faculties, leaving them childlike and helpless. Their bodies, their minds, and their instincts have atrophied in the absence of need or struggle. This is a chilling image: not merely of laziness, but of degeneration in the philosophical sense — of potential atrophy where capability once lived. (Wikipedia)

At first glance, the parallels to twenty-first-century societies might seem hyperbolic. After all, few of us lack agency outright, and we remain painfully aware of the world’s injustices. Yet, when one looks closely at the interplay between technology and human behaviour today, the metaphor resonates with surprising precision.

Automation and the Loss of Agency

One of the prominent trends of our age is the exponential growth of automation. Machines and algorithms now perform tasks that once defined the substance of human labour: driving, diagnosing diseases, managing finances, even composing music. What was once the domain of specialised tradespeople or rigorous study is now routine output from digital systems. This explosion of automation brings efficiency and convenience — but also an attendant loss of direct engagement with the processes themselves.

Consider the average smartphone user: for most tasks, we never see the mechanics beneath the interface. We swipe, tap, ask an AI, and receive a result. If a system fails, many users are helpless — unable to perform even basic tasks without the intermediary of a screen or app. The analogy to the Eloi begins to crystallise: a population adept at consuming results but alienated from the meanings and processes that produce them. (Mental Health America)

This distance from the underlying systems is not merely a matter of convenience, but of cognitive consequence. The sociologist David Collingridge articulated a dilemma in technology governance: by the time the impact of a technology is evident, it has become so embedded that changing or controlling it becomes difficult. In effect, we trade agency for ease, and the psychological fallout of this trade — the sense that we are passengers rather than drivers — cannot be ignored. (Wikipedia)

Dependency and the Tech Ecosystem

This loss of agency is mirrored in how younger generations relate to technology. Studies from mental health research show that heavy reliance on digital devices and platforms is nearly ubiquitous among young people near adulthood, with a majority reporting a heavy dependence on technology for everyday functions — from social connection to information to entertainment. (Mental Health America)

Some research suggests this dependency is correlated with higher anxiety and emotional distress — not because technology causes mental illness in a simple, direct way, but because compulsive use, constant digital feedback loops, and the loss of control over habits and attention can amplify feelings of anxiety and instability. (Mental Health America)

Most strikingly, modern studies on adolescent screen use link addictive patterns of engagement — not merely hours spent but patterns of compulsive use — to emotional problems, suicidal ideation, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. These findings indicate not only psychological stress but an erosion of resilience and self-regulatory capabilities among youth deeply embedded in digital ecosystems. (The Guardian)

If Wells’ Eloi succumbed to ease and lost their capacities over generations, modern society — especially among young people — is showing hints of that same pattern in behavioural trends: from diminished abilities to persist without external stimuli, to emotional fragility when devices are absent, to a reliance on automated systems rather than independent problem-solving.

The Illusion of Comfort

But here the analogy must be sharpened rather than stretched: we have not (yet) become feeble, incapable hominids. We have, however, cultivated layers of comfort that insulate us from hardship in ways that could subtly reshape character and capability. For the Eloi, every challenge had been abolished by generations of ease; for us, many challenges have been outsourced to technologies that mediate nearly every aspect of life.

As digital assistants manage our calendars, AI tools draft our text, automated systems handle logistics, and apps adapt our environments, the experience of mastering the world recedes. We may gain time in one sphere, but we lose depth in another. Without necessity, struggle becomes optional — and without struggle, the psychological mechanisms that build resilience, critical thought, and emotional strength are underused.

A telling metaphor is our response to technological failure. When our internet goes down, many of us feel not irritation — but panic. A glitch in the GPS can leave us disoriented, not because we lack curiosity, but because we have surrendered our navigational instincts to silicon. This isn’t just convenience — it’s a surrender of agency. (vida.id)

The Mental Landscape of a Digitally Infused Generation

Psychological research suggests that this isn’t an entirely imagined concern. Longitudinal studies show increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms among adolescents in recent years, often concurrent with heavy digital device use and the pressures of online social ecosystems. (Mental Health America)

These associations aren’t simple causal chains — technology doesn’t create mental illness — but the context of addiction-like patterns, comparison-driven social media, and feedback loops tailored for maximum engagement has reshaped the emotional environment in which young people develop. In some respects, what we’re witnessing is not the loss of ability, but the erosion of confidence, presence, and internal grounding: psychological analogues to the Eloi’s loss of survival muscle.

Agency as Antidote

Yet the comparison to the Eloi also reminds us that sheer ease alone does not determine destiny; social context, economic structures, and deliberate choice matter enormously. Wells’ Eloi were isolated on the surface, dependent without awareness of their dependence. By contrast, we remain deeply aware of both the benefits and risks of our technologies.

We debate automation ethics, AI governance, digital addiction, and the dangers of data concentration. We ask whether curricula should teach resilience alongside computational thinking. The very existence of these debates suggests that we are not passive participants in our own evolution — a distinction the Eloi never had. In fiction, the Eloi don’t know what they don’t know. In reality, we are increasingly conscious of our dependencies, anxieties, and the psychological costs of technological integration.

Moreover, human agency is more than the ability to perform tasks. It is the capacity for reflection, for choosing how and why we use tools — and it’s this capacity that remains at the forefront of the discourse around technology, education, and societal development.

Conclusion: A Call to Avoid Eloi-ness

To be an Eloi is not simply to be comfortable; it is to be unaware of the foundations that sustain comfort. That unawareness is the true loss Wells warns against. In many ways, our contemporary moment is not yet that dystopia. We still think, we still worry, we still debate our tools and our futures.

But there is a risk that, without intentional engagement, that awareness could be lost. If we outsource too much of the work of thinking, acting, and navigating life to machines and algorithms, the subtle atrophy of resilience and self-direction could accelerate. Becoming the Eloi would not happen overnight — it is a generational drift, a quiet disengagement from the challenges that shape thought and character.

If we are to avoid that fate, the antidote lies not in rejecting technology, but in reclaiming agency: teaching skills not just of operation but of understanding; cultivating resilience alongside intelligence; and ensuring that the comforts of automation do not become the cocoon that dulls our capacities rather than enabling our potential.

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed)

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed) Main feed (direct XML)

Main feed (direct XML)