| Flying in | |

| Camera: Panasonic DC-G9M2 | Date: 17-06-2025 06:09 | Resolution: 1788 x 1788 | ISO: 640 | Exp. bias: -33/100 EV | Exp. Time: 1/320s | Aperture: 5.6 | Focal Length: 150.0mm (~300.0mm) | Location: Scavenger Hide, Zaminga | State/Province: Thembalethu, KwaZulu-Natal | See map | Lens: LEICA DG 100-400/F4.0-6.3 | |

Over the past few weeks I’ve had the same conversation at least four times: before my trip to South Africa, at least twice while I was on my safari, and also after sharing my images for review. It starts like this:

Experienced Wildlife Photographer: "You need to use a shutter speed of at least 1/2000 s"

Me: "Why?"

EWP: "Because you have to, to get sharp images"

Me: "Why?"

EWP: "Because"

…

OK, in reality I don’t channel my inner toddler quite so directly, nor am I claiming to know better than the various EWPs. They do have some valid reasons, but I think that there’s also an element of "received wisdom" hiding very real technical and artistic options. The repeating nature of the discussion and my relative success with other strategies suggests that there is scope for more analysis. This is my take on that.

The technical decisions come down to minimising the risk of "missing the shot" – capturing an interesting subject, but the resulting image being of low quality, typically, but not necessarily, with unacceptable motion blur.

There are two sources of motion blur. The first is unintentional camera movement. In the olden days of film and non-stabilised lenses the golden rule was that the shutter speed should be at least equal to the focal length in mm, e.g. 1/800s if your telephoto lens is equivalent to 800mm. But it’s different now. A lot still depends on the photographer’s abilities and the physical size and weight of the camera and lens, but with modern image stabilisation most photographers should improve on that rule by 4 stops (a factor of 16), so should be able to hand-hold the 800mm lens at 1/50s. With the lightest mirrorless kit another factor of 4 or so might be possible. Shooting at medium speeds such as 1/250s really should not be an issue.

This does assume your own platform is stable. If it is moving, for example a boat, then you will need a higher speed, but again unless it’s pitching wildly in a storm you might get away with less than you expect.

The other source of motion blur is subject movement. Even a static subject may twitch, or may have the wind ruffling its fur. However the real challenge is an active subject engaged in deliberate motion. If you want to freeze that motion the required shutter speed increases as the subject size decreases. If you are trying to freeze small birds in motion then you really do need shutter speeds up well over 1/1000s, but that’s just not true with an elephant, where 1/100s will work almost every time.

| Playful baby elephant, Zaminga (Show Details) |

You might be surprised how far you can go with medium-sized subjects and still freeze the motion acceptably. The picture above is a tawny vulture in flight, captured at 1/320s.

Even smaller and fast-moving subjects may work at lower shutter speeds than you think. My "Kingfisher rising" shot is "only" 1/1000s. I do wish I had used a higher frame rate to get a greater choice of positions especially on the downward arc, but I’m not unhappy with the shutter speed.

| Kingfisher rising, Lagoon Hide, Zaminga (Show Details) |

In the interest of not missing the shot you might be tempted to dial in a high shutter speed and have done with it, but of course there’s no free lunch. Unless light levels are very high, such a high shutter speed means using a higher ISO, going to a wider aperture, or both. Very high ISOs result in very noisy images, which may end up "soft" as a side-effect of noise removal. Using a large aperture on a long lens results in a very shallow depth of field, and your shot may end up soft because you missed focus. Either way you miss the shot anyway, whereas a different exposure compromise might deliver a clean and accurately-focused image with some amount of motion blur.

That’s the technical choice.

The artistic choices relate to your priorities for the image, and how you want to portray motion. My first priority is that most of the subject needs to be in good focus. I’m not a great fan of images where a tiny sliver is in focus and everything else is a blur, including much of the subject. (The classic example is a wildlife portrait where the eyes are in focus but the end of the nose isn’t. Not only don’t I particularly like the result if done well, but it will result in a bad image if focus is even slightly off.)

This means that I tend to ensure I’m working at moderate apertures. I get some benefit from the effective doubling of depth of field with Micro Four Thirds (MFT), but I rarely work at less than f/5.6. Occasionally this does leave a messy background sharper than ideal, but I would rather err on the side of caution, at least for the first shot.

Next, I try to avoid very high ISO values. With modern Panasonic MFT cameras ISO 1600 will work reliably and produce usable images even without much post-processing. ISO 3200 is fairly reliable, but all images need post-processing with Topaz Photo AI or similar to denoise and sharpen them. ISO 6400 and above tends not to work for "portfolio"-quality images. Admittedly in this case the smaller sensor is a disadvantage and full-frame cameras should get comparable images a stop higher on ISO, but sufficiently noise-free images above ISO 10,000 or so are going to be a matter of luck.

The received wisdom appears to be "get the shutter speed, accept the noise", but I know I can live with an image with some motion blur more easily than one with massive amounts of noise.

Then there’s the question of whether I actually want to show motion or not. If a lion is lyin’ there and happens to twitch its nose at the wrong microsecond I get a blurred shot, and that’s a fail. However if it’s doing something more dynamic, I quite like to show that.

My first influence is my love of equestrian sports as a photographic subject. My objective is often a panning shot in which the subject horse and rider are sharp, but the background is intentionally blurred to show the motion. If there’s some blurring of the horses’ hooves, polo mallets or the ball, that’s fine, as long as they are recognisable, and I think it adds to the dynamic nature of the picture. Practice has taught me that the best shutter speed to achieve this is around 1/250s.

| Polo at 1/250s (Show Details) |

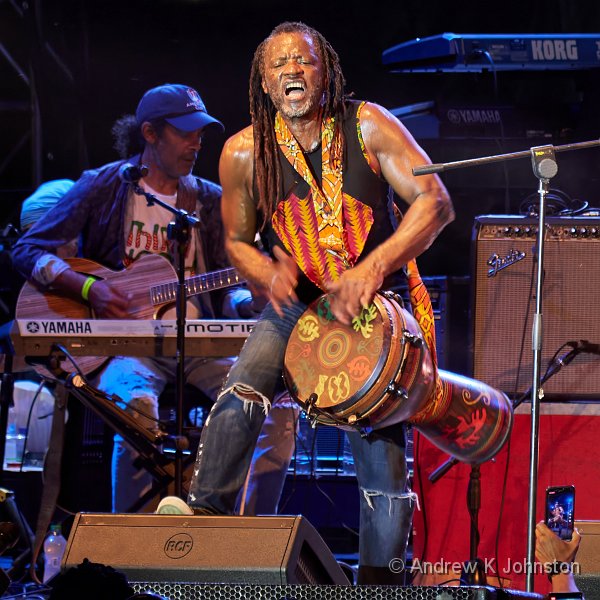

I also like to photograph concerts and human sporting events. If these are at night, or indoors, then I’m constrained to the event lighting which imposes a relatively slow shutter speed. Again, similar judgements apply. I want the subject clearly recognisable, but if, for example, their hands are moving rapidly, then that’s acceptable. Consider the following image: to freeze the drummer’s hands I would have had to use a shutter speed up around 1/1000s and that simply was not available, but I’m very happy with the rest of him, sharp at just 1/40s. His hands appeared to us as a blur anyway, and that’s what I’ve captured.

| Third World at Barbados Reggae Festival 2023 (Show Details) |

So how does this apply to wildlife photography? Here’s a picture of a lioness running at 1/250s. That speed was to some extent imposed by very low dawn light, and also she started moving just after we arrived at her location and my camera was on settings from a previous subject. However I think it works. Yes, there’s some motion blur of parts of her body as well as the background, but to my mind that expresses how fast she was moving. A "frozen" shot at 1/2000s, had it been possible (it wasn’t) would not have communicated that.

| Running lioness, Zaminga (Show Details) |

Of course, you can take this a lot further, and that’s a pure artistic choice. For example, Richard Bernabe has a wonderful image of a moving herd of impala at 1/20s (See here). With wildlife I probably wouldn’t go that far, but I have experimented with dance and fashion subjects, so never say never.

| Venice Carnevale, 2009 (Show Details) |

Modern kit allows us to work at higher speeds than would ever have historically been possible. Modern software such as Topaz Photo AI cleans up and sharpens images which might previously have been deemed inadequate, and I certainly make active use of it – several of the shots on this page have benefitted from at least noise reduction and basic sharpening. It’s certainly possible to "cheat" some of the technical limitations in a way which has not previously been available. However, to paraphrase the famous quote from Jurassic Park, "you were so occupied with whether you could produce a very sharp image, you didn’t think whether you should".

For my part if I am trying to freeze the movement of small, fast animals I will use a faster speed. If I’m looking for artistic blur then I’ll use a very slow one. Most of the time I’ll stick with something in the range 1/50 to 1/500s, and embrace rather than eliminate subject motion.

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed)

Thoughts on the World (Main Feed) Main feed (direct XML)

Main feed (direct XML)